Leper Knight

Knights of the Order of St. Lazarus.

54mm White Metal figures from Pegaso

Article in Military Modelling magazine in 2008

I've been toying with the idea of doing a couple of knights for some time now, and came across a book recently detailing this order by David Marcombe.

The book is a little bit on the "dry" side, being very much a pure reference history of the order, from its beginnings during the first Crusades in the Holy Lands, up to the present day as a charitable, non-military group.

During the middle ages, leprosy was viewed in quite strange ways. On one hand, it was believed by some to be a blessing from God, marking the afflicted as particularly beloved to their deity. Bearing in mind of course that the name "Lazarus" for which the order is named, means, "God is my help".

On the other hand, the terrible ravages that it caused, the debilitating and horrible disfigurement, caused people to shy away from sufferers, shunning them and seeing them as being marked for their sinful ways.

The common man or woman who had contracted the disease would probably be forced out of their homes, to become beggars, shunned by the masses, and if lucky, taken in to communes to be cared for by others suffering from similar depredations. Their relatives might, if they came from a particularly caring family, tend to them, dependent again on how kindly the family were, and of course how rich.

The fighting orders of the day, the Templars and Hospitallers, had their own problems with leprosy, particularly coming into greater contact with it in the Holy Land as the Crusades pushed further and further east.

The Order of St. Lazarus is very likely to have taken its name from one of the five men going by that name in the Holy Bible.

The favourite donors being both from the New Testament, the obvious and most likely one being the Lazarus, brother of Mary and Martha, who Jesus raised from the dead. The other contender being Lazarus the Beggar, afflicted with sores ( possibly an allusion to leprosy ) and who finds favour in Gods eyes as a result of his beliefs and actions.

Leprosy had been almost endemic since Roman times, particularly in the warmer regions of Eastern Europe, and during the 12th Century, it could have been on the rise. There had been a leper hospital established in Jerusalem in around 400 AD, by the then Empress Eudoxia, wife of Arcadius, but this in unlikely to have still been in existence by the time of the Crusades.

The order seems to have grown from a hospital in Jerusalem founded in around 1099 by crusaders, and is recognised as a Hospitaller institution in 1130. It was funded by the donations of brother knights from most of the other orders, and probably also some benefactors outside of the knightly ranks too.

After all, leprosy didn't respect rank or wealth, and to give to the order now, might have been a resting of the conscience that you might need admission to its halls some time later.

The Holy Land was, as most will admit, a large, spread-out battlefield, with fortunes of the Muslim and Christian causes rising and sinking with an alarming regularity. Jerusalem, as the founding place for the Order of St Lazarus, was attacked in 1186, and fell to the Muslims in 1187. The order had to move during this time, and was re-established in the city of Acre.

Although entry into the Order of St. Lazarus was compulsory from some of the other orders by 1260 - should you be unlucky enough to contract leprosy - there were also a few volunteer brothers who were healthy. This was probably the whole of the problem though. There were a majority of sickly and disabled knights, attempting to perform military tasks that were in realistic terms, far beyond their abilities.

Although the knights might well have been little more than a PR exercise, "A last desperate attempt to stop the incursion of the Infidels with an army of the living dead", and after all, the layman in the medieval world would probably find this an appealing idea, that of chivalrous knights fighting far from home, even thought they were sorely afflicted; one can't help but look at their success rate.

Or lack of it.

To be brutally honest, they were.....well, not very good.

Every action that they had a major involvement in, and that can be reliably traced, was a total cock-up. They seem to have fulfilled a dual role; it is thought, being perhaps a scouting group, at a distance from any main force, or possibly as a free-ranging group of volunteers rather than properly indentured knights.

Either way, in one action that is detailed for history, a group of Leper Knights thought to attack a village near to Jaffa, probably with the idea of taking booty and supplies from said place, only to be fallen on by a Saracen force. Templars were sent to aid the Lepers, but only around three or four of the knights escaped with their lives.

In the defeat of the Crusaders at La Forbie in 1244, all the Knights of St. Lazarus were killed, as too at the disaster at Marsuna, where the King, Louis IX was captured by the Egyptians.

To be fair, Nicholson, a commentator of the day, says that the knights of the order were reckless to the point of being suicidal. And, with the amount of pain, not to mention the loss of some appendages to this disease, the fact that any of the order were game enough to even consider going into battle is a sobering thought. These guys were not just brave; they were something special.

In 1253 Innocent the IV altered the rules governing the order, as up until this time the Master General - the fella in charge of the knights - had to have contracted the disease. Innocent IV changed this, so that a healthy knight belonging to the order could take this position, which would hopefully strengthen their military talents. From this time on, it would seem that more healthy knights were encouraged to join the order, but even so, it was still a small muster that saw Acre being defended in 1291 when the Sultan Of Cairo laid siege to the city.

The knights of St Lazarus fielded twenty-five men, and it's not too bad, considering that the Templars and Hospitallers only had around thirty each in their ranks. However these two latter orders could call on outlying garrisons to fill out that number quite considerably.

During this siege, the Christian knights made a foray, ostensibly to destroy the Sultans siege weapons, if they could. The luck of the St Lazarus knights was in full flow though, as the horses of the force became tangled in tent lines as they attacked the besieging army. Many knights were killed, some number of these would have been the St. Lazarus knights, and one can only wonder at how hard they would have fought, retreating back to the tenuous sanctuary of Acre’s walls. This attack took place on either the 14th or 15th of April of 1291.

The Sultan finally broke the siege, entering the city on the 14th of May, and the carnage that ensued was terrible indeed. Needless to say that none of the St. Lazarus knights survived at the end of that day.

The order does however seem to have a knack of regenerating. It is still extant today, being a non-military, charitable order. It just shows, I suppose, that even men afflicted with such a terrible disease as this could manage to fight in major engagements, and were the forerunners of such a long lived organisation; A creditable epitaph to them at least.

The models.

Having decided to portray a couple of knights from this order, I had to then find a pair of likely models, and I turned to my favoured purveyor of all things small and metallic - Pegaso.

Pegaso have been rather profuse with releases this last few years, revealing some proper little gems, ones that I certainly couldn't leave on a vendors shelf anyway. For this vignette, I chose two pieces, the "Warrior Monk" no 54-135, and the Holy Land knight no 54-151.

Both of these are in action poses, and although the Holy Land knight is standing atop a rock, it should be easy enough to combine the two of them into a small vignette.

Whilst I wanted them to look threatened, I also wanted them to seem defiant. In this I was trying to portray the hopelessness that these men must have felt, to be in temperatures and dust that would make their disease even more debilitating than it would be in a more northern country.

The hardest part, was trying to give the impression that they were suffering from leprosy, without caricaturing the point.

Leprosy affects all parts of the body, but “hacking off” a couple of fingers, in this case would be impractical. How would a knight hold a sword effectively with only two fingers and a thumb ?

I did then think of various braces and ties that could have been used, but it seemed simple, and more subtle, to hint at the disfigurements. I therefore chose to extend the scarf around the Holy Land knight’s head, so that it covered part of his face.

I chose to leave the monk whole and healthy looking, one reason being that it is mentioned that some healthy knights entered the order to care for their more afflicted brethren, and this could be one such.

The other consideration here is that the figures are quite well wrapped up. There’s not that much skin left bare, even on the face, and it doesn’t leave much of a canvas for the would-be sculptor to alter.

Colours used

The colours I have chosen to use follow the colours still used by the order today, that of a green cross on a white background.

In these modern times however, a couped cross is used. An example of the present day cross is shown in this photo. However, the reason I used a passion cross is that the older records that have survived, for example the corbel stone on a pillar in Grattemont in Normandy, show the earlier, and simpler passion cross form being used.

There are problems with using older references though. For a start, most commentaries that are still existent suggest a green cross on a white field for the heraldic colours. The corbel at Grattemont flies in the face of this by showing an off-white cross on a very dark green field. I’ve also seen the passion cross symbol extended to the edges ( or more like past the edges ) of the shield in heraldic pictures, rather than the passion cross with space around its extremities, as shown on the Grattemont corbel.

I’ve tried therefore to hedge my bets, by sticking with the colouring more commonly accepted for holy orders, i.e. a coloured cross on a “metallic” field, but have remained with the passion cross, separated from the shield edges.

This form looks simplified, would be relatively easy for a squire to reproduce, and is in keeping with the older references that I have.

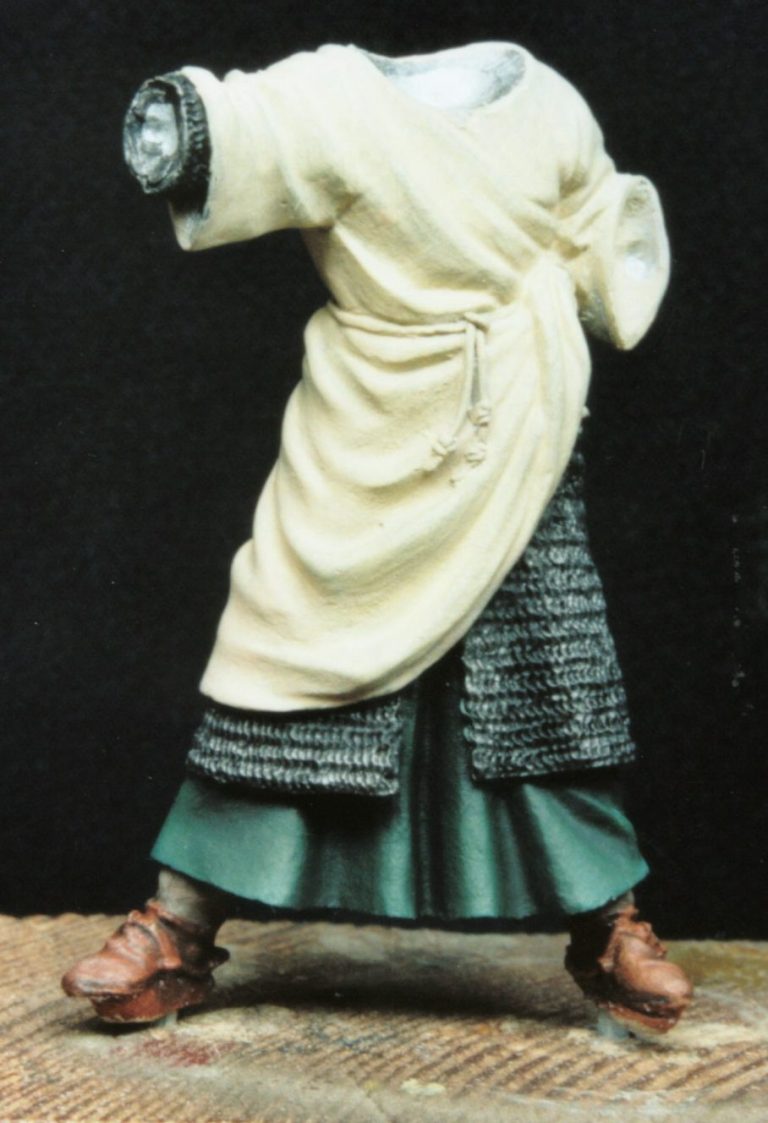

I chose to do the clothing using both the references, and also using a little common sense. Green seems to feature heavily in the colours quoted, both in modern day and more ancient texts. But any dark colour draws heat, and realising that desert peoples have long used either very dark coloured clothing ( to radiate the heat off the wearer ), or better still, to use a lighter colour to actually reflect the sun’s effects, I chose to paint one knight with his green vestments in place, and the monk with an off white habit, hopefully reflecting all that heat away from the wearer. The monk’s affiliation are both shown by the shield that he carries, but if there were any doubt, the green is also carried over onto the skirt showing under the mail coat he wears.

The models

The parts for these two models can be seen in photos #1 and #2. The monk is a whole lot less complex than the Holy Land knight, although that hand to sword attachment looks distinctly tenuous. The weapon the monk has seems to be classed as a glaive. It’s basically a single edged large-scale carving knife on a wooden handle. The handles can be of various lengths, anything up to making the weapon look like a spear.

Arming the monk with this instead of a sword makes for a little more interest, not simply because the shape is somewhat different, drawing the eye of anyone viewing the piece, but also adds a continuing danger of it being broken off. I said that joint between the hand and weapon was dodgy !

Um… I’ve had to glue this back on to the finished model three times so far, barring holding a sign saying please knock this blade off, I couldn’t wish for a more easily hit target. I have to admit though, that I was the culprit on two of the occasions !

Anyway, needless to say, both models are nicely produced, Pegaso at their best in fact. Both come in sturdy little boxes, lined with foam, and the parts are nigh on perfect. There are a few mould part lines to clean up, but these are easy to get at and deal with in the main. The ones I missed on the first outing with file and craft knife were on the monk’s ankles.

Priming the figures with a light colour, in this case a light flesh tone acrylic, showed the error of my ways, and the missed line was quickly removed ( don’t tell anyone I missed something, it looks distinctly unprofessional ! ).

I’m not sure if I’ve mentioned it before, but adding a little Isopropyl Alcohol ( either available from chemists in a pure form, but expensive, and they look at you rather strangely, or in the form of windscreen / windshield wash liquid ), to the initial coat of acrylic paint, will stop it beading on the model. This works on either resin or white metal, and allows the paint to be applied quite thinly.

The confusing thing being that a little addition of Isopropyl to the paint seems to thicken it up, adding a little more then thins it. Don’t however, be tempted to add further coats using this method of thinning the paint, as the alcohol attacks the dried paint already on the model, and you’ll end up with a real mess.

Applying subsequent coats of acrylics thinned with water is fine though, and the undercoats can be built up as normal.

Before starting the painting I made the relevant additions to the Holy Land Knight, using some small amounts of Magic Sculpt putty to do the extended headscarf.

As usual, I began painting the models whilst they were still in kit form, and photo #3 shows the Holy Land knight’s feet undergoing alteration ready for a pin to be drilled up into them.

Pegaso helpfully add location blocks to the bottom of most of their figures feet. This is good if you chose to use their bases, and particularly to set their stance up correctly, if like this model, the legs come as separate parts.

However, if the model is going to travel about a fair bit, then it’s probably best to add some extra strength to the joints, and so that the drill bit doesn’t slip off the foot and damage the model, or even worse, damage me, I cut part of the location block away ( as with the foot on the right of the photo ) so that I’ve got a flat area to apply the drill to. It’s even better to add a small locating dimple either with a knife blade, or a drill in a pin-vice, before starting to drill with a minidrill. Remember, safety first.

In photo #4 I’ve joined some of the parts together. Before fastening these parts together, I painted the base colours onto the mail skirt, and the linen coloured lining to the surcoat. These are areas that I just wouldn’t be able to with a brush once the model was glued together.

Once these inaccessible areas are finished, I could fasten the parts together and begin to file and fill the joint at the back of the surcoat and across the belt.

I added the brass pin once the parts had been glued and had a chance to dry. Drilling a hole through the body and down into the leg, and adding a pin. This was left standing proud of the upper body casting, locating into a hole that had previously been drilled into the neck.

There is also a pin strengthening the left arm joint, as this has the weight of both the arm and shield to support on a relatively small area that can be glued.

Photo #5 shows the rear of the model, now that the joint on the lower surcoat and belt have been fixed up and painted.

Once the belts and gloves are painted, along with the scarf around the helmet and shoulders, the only thing left to do is glue the bits together.

The monk was quite a lot simpler to do, using basically the same palette of colours as the knight, and the same methods too, he can be seen in photo #6 with the main casting having had everything barring the off-white being completed.

The habit gave me a few problems with its shading; mainly because of the sweeping creases. I initially painted this with oils, using the Yellow Ochre and Titanium White, and then adding some deeper shadows with some Sepia oil paint.

I’ve been playing about with this colour for a couple of months now, having got some shortly after Hardy Tempest mentioned it in his first article.

As with any new colour, it takes a little practice getting used to it’s application, but after a couple of hit and miss outings with it, Hardy seems to have a point about it. It works a treat.

Well, it did up until this model. I think I was just having a bad day, because it’s the only time I’ve not had success with it since the first couple of practice runs. However, it just didn’t seem to work, so I opted to use some thinned Tamiya Smoke coloured acrylic ( basically the same colour really ) and built up the shadows with this.

The base.

This is where I wanted to really get the feel of the desert, some dry, dusty back of beyond.

The problem is, sand doesn’t tend to make for an interesting scene, and certainly not in the few inches of space I had to play with. I certainly wasn’t going to manage an arresting desert vista, with sweeping dunes and a complement of camels and palm trees.

Instead I found a couple of interestingly craggy rocks – an old piece of chalk from the garden was the main basis for this. I then posed the models near it, working with as small a space as I could. Having drilled into the chalk to take the pin from the Holy Land knight, I found that I’d have to use some Milliput to build up a section of the rock for his left foot to perch on. The monk however could just sit on the flatter “ground” at the front, this being made with some of the leftover putty.

Having decided on the models positioning, I constructed the groundwork, and then masked off the base so that I could spray the various bits of putty and rocks with an airbrush.

For this I used the Tamiya colours – beginning with Flat Brown ( XF10 ) to build up the shadow areas, and then spraying on Desert Yellow ( XF59 ) to block in the mid-tones. Some final shadows were added with a wash of Burnt Umber oils, and then the highlights were enhanced with a mix of more Desert Yellow and some Flat white ( XF2 ).

The models were added in to their locations….and they looked too clean. Yup, that dusty looking base looked just that. Too dusty, whilst the figures were lovely and pristine - it had to be changed.

I solved the problem by lightly dusting the lower halves of each figure with some of the Desert Yellow, using the airbrush to build up the dusty look of each model. Because the dust is being added slowly, I mixed the paint up with a lot of Isopropyl alcohol ( roughly 10% paint to 90% alcohol ), the effect can easily be controlled so that the colours of the clothing aren’t lost.

This married the models to the base very well indeed, and it’s a method I’ll explore more in the future, as I feel that a lot of my models would benefit from “dirtying down”.

As usual, Pegaso have delivered with these two little offerings. I really do like the recent kits that Pegaso have been putting out. They used to do some good models, and I’ve always liked most of what they produced, but they don’t seem to have rested on their laurels at any point in the last few years.

The unsung hero of the piece is of course the sculptor, and in this case, the models were both sculpted by Gianni la Rocca.

References :

Leper Knights – David Marcombe ISBN0-8115-893-5 ( in particular the references about colour for shields on page 27 ).

Also the Order of St Lazarus website – www.stlazarus.net/

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.